Children and Parents Talk about Language

Riya and I are sitting at a café, talking about her experiences as a child of multilingual parents. I ask her how my class, a community-engaged course in the UMass Amherst English Department, shaped her understanding of multilingualism in her family. Riya says,

Asking my parents about language is something I’d never done. Having the space for them to be able to tell me about these experiences… it just made me feel so much more connected with them in a way that I’d never been before.

In my class, UMass students partner with staff and students at ILI to work on writing and language projects. UMass students support ILI students’ writing and English language learning; ILI staff and UMass students collaborate on curriculum development and revise homestay materials.

During this community work, I ask the UMass students to interview their parents about their language histories and write about what they find out. The assignment guides students to make connections between the language and literacy stories developing at ILI and the language and literacy stories in their own families.

In the years I’ve taught the course, all of the UMass students report having never asked their parents about their experiences learning or using multiple languages. And they treasure the chance.

As a scholar at UMass Amherst, I study the resources that multilingual people use to write—their savvy understandings of how language and literacy works in the world. In my current research on our ILI-UMass partnership, I’ve found that children of multilingual parents deeply value the opportunity to reconsider how multilingualism has shaped their family.

I have begun to call these opportunities “literate mending,” a kind of writing that helps people recognize and reconnect their family’s fragmented language histories. When multilingual writers engage in “literate mending” they use writing to mend, or put back together, language identities that have been fractured by judgment of accent, shame and fear of language stigma, or de-valuing of certain language varieties.

Riya Says “Oh Crap”

The case of Riya helps explain this. Riya is a Tamil/English bilingual Indian-American who was an undergraduate English major when she was involved with the ILI partnership. Riya was born and raised in the U.S., traveling occasionally to see extended family in India.

During her involvement with ILI, (her project was co-designing ILI’s driving curriculum), Riya describes uncovering tension in her family’s language background.

In a research interview with me, she talks about the disappointment she felt in the negative treatment of multilingual immigrants depicted in articles we read in class:

When we did all these readings I was like, how can people be like that, how is this the way things are? And then the second you were like ‘reflect on yourself,’ I was like ‘oh crap, I don’t want to.’ I had to confront myself and the fact that I was that person.

Riya is referring to the moment I asked students to consider their own role in how language hierarchies are formed in everyday life, especially how standard forms of English become highly valued. Riya wrote about the embarrassment and shame she felt about her parents’ accented English growing up. She wrote about the pride she’d always felt in her flawless English-language writing. In her final essay, she explains simply, “I partook in the perpetuating of language subordination, putting down any and all other languages in the process.”

in everyday life, especially how standard forms of English become highly valued. Riya wrote about the embarrassment and shame she felt about her parents’ accented English growing up. She wrote about the pride she’d always felt in her flawless English-language writing. In her final essay, she explains simply, “I partook in the perpetuating of language subordination, putting down any and all other languages in the process.”

In her interview, she explains that the class’ writing activities gave her space to talk to her parents about why and how they experienced learning English, how they used their own Tamil to navigate that learning, and why they encouraged Riya to maintain her multilingualism.

Because of these writing activities, Riya began to mend her shame around her parents’ multilingualism and critically view her own. Rather than place English on a pedestal, she fostered pride in using the entirety of her language repertoire as a member of a larger Indian community. She explains in full:

The class, really what it did was take the information I had been very accustomed to and actually exploit it, these deep, intertwined connections I had never explicitly addressed but knew were there. It was this very weird re-understanding, if that’s a word. Just asking my parents about language is something I’d never done. Having the space for them to be able to tell me about these experiences…it just made me feel so much more connected with them in a way that I’d never been before. It made me feel so much more connected with my identities…It made me feel so much more whole-some and so much more connected with those parts of me.

Riya does not use “wholesome” here to mean good, ethical, or moral. The larger interview conversation shows that she means that parts of her could be “connected” to make a whole.

Writing about her parents’ interviews opened space for Riya to re-see her family’s multilingual history. Riya’s “very weird re-understanding” shows how writing about her family led her into “the deep, intertwined connections” about multilingualism that she intuited but had never had the chance to name.

This notion of mending—connecting to make whole—echoes with force across the 41 participants in my study of the ILI-UMass partnership. I followed these echoes by tracking words that indicated what participants understood about multilingualism.

For example, one pattern indicated a theme of connection, including participant uses of words like “whole,” “bridge,” “reconstruct,” and “repair;” another pattern indicated a theme of separation with mentions of “break,” “separate,” and “fracture.” I found that these two themes—connection and separation—worked not in opposition but in tandem during examples of literate mending.

That means that multilingual writers don’t just become aware of their language pasts, connect with their families, and feel better. Instead, mending means writing through the bad and the good—the disillusion as well as the inspiration—to come to a critical recognition of the language wisdom one’s family and community already has: the “deep, intertwined connections” they may have “never explicitly addressed but knew were there.”

Why Multilingualism Matters

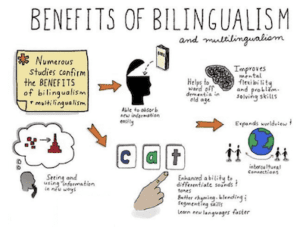

As Riya’s case shows, multilingual people, including those learning English as an additional language, benefit from thinking about all of their languages as assets to their learning, expression, and identities. In this way, focusing on what language users have rather than what they lack can help unwind some of the damage carried out by language subordination.

Language subordination is an often-racialized social process that devalues certain languages (and language users) and can lead to language bias and discrimination (see Rosina Lippi-Green’s model). Everyday interactions around accent, dialect, and multilingualism can perpetuate language subordination by punishing people for communicating or expressing themselves in ways they identify with. Even those who espouse progressive ideals may carry out exclusionary language practices like interrupting someone to correct their grammar or demanding English language use in public.

The “monolingual mindset” dominant in the U.S. also can cause families to fear that encouraging their children’s heritage languages will impede their English language learning and general success. Further confusing is the tendency to devalue or even punish immigrants’ multilingualism while lauding monolingual individuals’ learning of additional languages.

Plenty of research shows the intricate benefits and challenges of multilingualism, but most linguistically diverse families simply don’t have a chance to talk about it. Engaging in literate mending is a form of language justice that not only celebrates language diversity in families but more so recognizes the uniquely critical and expressive skills of those who communicate across language difference as a matter of daily life. Therefore, we might consider how community settings like ILI provide the kind of intergenerational conversations literate mending demonstrates.

Plenty of research shows the intricate benefits and challenges of multilingualism, but most linguistically diverse families simply don’t have a chance to talk about it. Engaging in literate mending is a form of language justice that not only celebrates language diversity in families but more so recognizes the uniquely critical and expressive skills of those who communicate across language difference as a matter of daily life. Therefore, we might consider how community settings like ILI provide the kind of intergenerational conversations literate mending demonstrates.

Because it values all of its students’ languages, ILI offers unique opportunities to foster literate mending as well as other justice-based approaches to multilingualism. In her own research interview with me, ILI Executive Director Caroline Gear explains:

We are not just a school to learn English. We are much bigger…It’s English also, not English only. We want to make sure that students have their own voice, not only with English, but if they have something to say they can say it in their first language, too, and not be shut down. …In our Free English Program, people who are in similar circumstances at a variety of different levels and language…communicate in their first language with each other to talk about what they are learning in the classroom, but also broader topics of life. I think it is really important—we want to create a safe environment where people can take risks. If you are always being shut down to only speak English, it will shut you down in more ways than you can even imagine.

As ILI and our UMass team move forward in our partnership together, we plan to make space for just that: writing workshops and other literacy opportunities that bring adult children and parents together, on purpose, to write about their language values, multilingual communities, and vibrant language lineage.

Rebecca Lorimer Leonard is an Associate Professor in the English Department and Director of the Writing Program at UMass Amherst. She teaches undergraduate and graduate courses on language diversity, literacy studies, and research methods and guided some of her students in working with ILI on our MA driving curriculum, tailored to the needs of immigrants and refugees.

-

Lorimer Leonard, Rebecca. “The Role of Writing in Critical Language Awareness.” College English 84.2 (2021): 175-198.

-

Lorimer Leonard, Rebecca. “Feeling ‘Whole-some’: How Transnational Writing Can Mend Literate Fragmentation.” Teaching and Studying Transnational Composition. Eds. Bruce Horner and Christiane Donahue. Modern Language Association, 2022: 190–206.

-

Lorimer Leonard, Rebecca. “Writing to Mend Literate Fragmentation.” Writing on the Wall: Writing Education and Resistance to Isolationism. Eds. David Martins, Brooke Schreiber, and Xiaoye You. Utah State University Press, 2023: 89–105.”

Related articles about learning Spanish, studying French, taking Portuguese classes, and more:

- Great ways to learn Spanish online and why it’s important.

- Top movies to help you learn English and love the language more

- Top 7 reasons to speak and learn Spanish fluently in the USA.

- World of jazz: Interview with Andy Jaffe, a Portuguese and Chinese language student living in the USA.

- Spanish is Darlene’s Superpower: Interview with Darlene, a Spanish language student living in the USA.

- Kathy Learning Spanish (again): Interview with a Spanish language student living in the USA.

- How Alice Flexes her Brain Through French film: Interview with a French and Spanish language student living in the USA.

- Charles the language person: Interview with an Italian and German language student living in the USA.

- Takehiro Rises: Interview with an ILI English student from Japan who built a career in the USA

- Marco Bittencourt brings a lifetime of multicultural experience to teaching!