By Steve Pfarrer

On a recent evening at Northampton’s International Language Institute of Massachusetts, the students in Rachel Martins’ English class were studying the language in an unusual way: through a variation of the classic card game Go Fish.

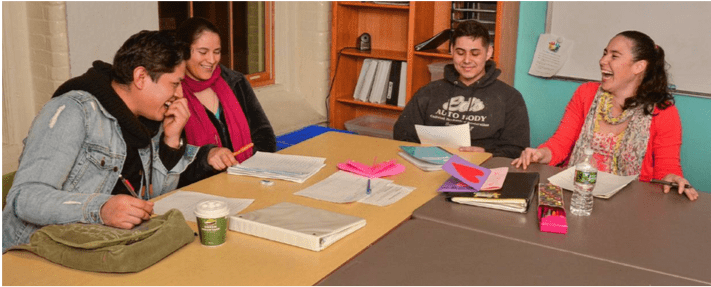

Instead of using a standard deck of playing cards, Martins passed out handmade cards, blank on one side and with a verb on the other. The six students broke into two groups of three each, with one person in each group shuffling the cards. Martins had some praise for one student’s deft work: “Ricardo, you should think about getting a job in a casino,” she said, and laughter rippled around the room.

The students, all originally from countries in South or Central America, or with close connections there, were working on conditional/future expressions. In this exercise, each took a spread of cards and then used the verb on a card as the root of a question, like one posed by Luis Azogue to Carmen Quillay: “If you play soccer, will you let me play?”

The object was to see if a second person had a card with the same verb, and then take that card. But Quillay looked at her cards, shook her head and, a smile playing on her lips, said, “No, I won’t — go fish.”

Azogue, with a quick laugh, drew another card from the pile in front of him.

At the other end of the table, Martins huddled briefly with Blanca Sandoval and Ana Correa to answer a question, then stood nearby as Sandoval looked at a card in her hand and said “If I drink a glass of water, will you give me another one?” Correa shook her head: “No, I won’t.” Sandoval smiled and drew another card.

If your memory of studying another language is of sitting at a desk, conjugating verbs in a notebook while the teacher scribbled on a blackboard, the International Language Institute (ILI) will seem a very different place. The emphasis on classes here — in English, Spanish, French, German, Italian and other tongues — is on immediate verbal engagement, speaking the language as much as possible, with visual and aural prompts to help you.

Above all, classes at ILI are designed to be fun, with material that students can relate to: “student-centered learning,” as Executive Director Caroline Gear puts it.

Alexis Johnson, ILI’s co-founder and the institute’s former director, is even more direct. “I want to hear laughter coming out of the classroom,” she says. “Our goal is to get people speaking and enjoying [a language]. It’s OK to make mistakes — there’s nothing to be embarrassed about.”

Those goals have been at the center of ILI since it first opened its doors in 1984, with a tiny staff and budget and a handful of rooms in a former thrift shop in Brewster Court. The nonprofit organization has long since broadened its mission, offering language instruction not just to adult students (college-age and older adults) but to employees of regional businesses and organizations — Spanish, for example, for companies with Spanish-speaking clients or customers. Training teachers to work abroad, teaching ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages), is also a priority.

It’s a stretch to say the organization is a well-kept secret, but you might say it hides in plain sight. Its rambling offices and classrooms are tucked away at 25 South Street in downtown Northampton, inside the Old School Commons building (now made up mostly of condominiums) across the street from the Academy of Music. Yet Gear says ILI serves about 800 students a year — including at Hampshire College, where ILI has managed the Spanish program for 35 years — and the institute is looking to expand its offerings and increase its visibility in the language school field.

Though Gear says it’s hard to gauge the direct economic effect of having foreign students coming to Northampton to study, she notes that according to analysis by a nonprofit group known as NAFSA, an association of international educators, international students contributed $39 billion to the U.S. economy in 2017-18, and created or supported over 455,600 jobs.

Free classes in English for immigrants and refugees, and for people living in the country temporarily, are also a big part of ILI’s programming, and the institute has built partnerships with several area colleges. And to help foreign students acclimate, ILI enlists volunteers to spend time with them and host families to give them a place to stay.

“A lot of people are used to language schools being in big cities,” says Gear. “But here you have a big-city feel with a much easier lifestyle, with access to schools and art and culture … we just have to get the word out about that.”

And at a time when debates in the U.S. about immigration and building a wall on the Mexican border have become flashpoints for so much angry rhetoric, Gear and other ILI staff are clear about which side they stand on. They see language instruction as a central means of building greater cultural understanding and appreciation in an era of ever-growing global interaction.

Gear points to a sign that’s taped to the institute’s front office window and repeats its words: “I say to our students, ‘Everyone is welcome here.’ ”

During another recent day at ILI, Samira Artur was leading students in a beginning Spanish class — and doing so entirely in Spanish. She had taped pictures illustrating various activities, such as “montar en bicicleta” (to ride a bicycle) and “limpiar la casa” (to clean the house), along the classroom walls, and she’d written some basic vocabulary words and sentences built around the word “viajar” (travel) on a whiteboard.

During another recent day at ILI, Samira Artur was leading students in a beginning Spanish class — and doing so entirely in Spanish. She had taped pictures illustrating various activities, such as “montar en bicicleta” (to ride a bicycle) and “limpiar la casa” (to clean the house), along the classroom walls, and she’d written some basic vocabulary words and sentences built around the word “viajar” (travel) on a whiteboard.

Artur, who speaks Spanish, English and her native Portuguese, asked the seven seated students to stand, break into three small groups and take turns asking each other some simple questions based on the picture immediately behind them. She moved around the room, listening and answering a question — in Spanish — then pronounced herself satisfied: “Excelente. Muy bien.”

Next she passed out small cards with colored, cartoon illustrations of people in various poses — shivering with cold, for instance, or biting into a sandwich — and other cards with a word or expression on them. The students had to match the words and pictures, and Artur helped out by pantomiming some of the words and illustrations; she wrapped her arms across her chest and mimicked a shiver, saying “Que es esto?” (What’s this?)

“Frio?” (cold) one student suggested. “Si, bien,” said Artur.

Before the class, Artur explained that ILI’s philosophy is to get students up and running with a spoken language as quickly as possible. In her class, she’ll take the occasional question in English if someone doesn’t understand something or can’t pose a question in Spanish, but the emphasis is on making students comfortable, on a very basic level, with expressing themselves in Spanish and making connections in the language. Figuring out the details and exact grammar can come later.

“You can use context, pictures, games, and gestures to explain a lot,” says Artur, who has taught at ILI since 2009 (she’s also taught Spanish, using similar techniques, at Hampshire College since 2010). With beginners, she notes, the conversations take place in the present tense and are focused on daily activities, food, numbers and other familiar things. “It’s things they can talk about.”

Artur also teaches English at ILI, and given that students in those classes can have any number of native languages, there’s no one “fall-back” language she can offer them. Still, she says, “I can connect with them” based on her own experience. A native of Brazil, she began learning English and Spanish in elementary school; then her family moved to Maine when she was 14, and she discovered her English wasn’t good enough to get along in her new school. She struggled for a few years before learning English largely through immersion, then studied in Spain as a college student and got her master’s degree in Spanish from the University of New Hampshire.

Gear says most members of the ILI staff — eight full-time employees, and 17 part- time ones — “have lived in different places, had lots of different experiences. They can relate to our students who have just come here and need help navigating the system.”

Gear, who began at ILI in 1986 as a part-time Spanish teacher, has a similar background. She studied French for four years in high school and learned to read and write — but not speak — the language. Then she spent a “gap” year as a Rotary Youth Exchange student in Peru, where she says she learned the importance of actually speaking a language. She went on to study Spanish and Spanish literature as an undergraduate and graduate student, studied in Mexico for a year, then taught English in Spain.

The ILI approach works for Aaron Gerber of Northampton, a software engineer in Artur’s weekly class. In an email, he said he’d taken a year of Spanish in high school and over two years of college French and “neither of them clicked for me. Those experiences left me thinking I just wasn’t good with languages.” But after picking up two local languages during a stint in the Peace Corps in Niger, he says he realized learning a language “really comes down to the amount of time/effort spent.”

Looking for a new experience outside of work, he signed up for the ILI Spanish class, which he says has given him the “conversational piece” he never had. “And it helps to celebrate your mistakes and accept the discomfort of a little confusion throughout the learning process…. Being encouraged to speak and figure out what’s going on in class has been a wonderful experience.”

Another student, Kate Cadwgan, says she often comes across Spanish “in travel and day to day life. I always wished I could communicate! Being fully immersed in Spanish during the class was hard at first but has helped me think more quickly within the language.”

Some of the students in Rachel Martins’ bi-weekly English class say they’re also seeing progress. They often spend their work days around other Spanish-speaking people, they say, so it can be tough to find a time to use English; the class helps fill that gap.

Blanca Sandoval, for example, originally from Guatemala, says she didn’t know any English when she came to the U.S., even though her husband speaks fluent English (he is also originally from Guatemala but was raised primarily in the U.S.). But Sandoval, of Florence, says she’s steadily improved since she began taking classes at ILI several years ago: “Speaking can still be hard, but I understand [spoken English] better.”

And Ana Correa, of Hatfield, says her two young sons, ages 6 and 9, have been part of her inspiration for learning English. She’s originally from Colombia, her husband is American but also speaks Spanish, and her boys are bilingual. The family tends to speak Spanish at home, but her sons’ English is well advanced, she says.

“They say to me, ‘Mommy, your English is so bad,’ ” Correa said with a laugh. “So I say, ‘I will get better.’ ”

Alexis Johnson, who stepped down for the director’s position at ILI three years ago, says she misses the organization, though she still does some occasional teacher training there. “It’s my baby,” said Johnson, who speaks several languages, including Spanish, Catalan and French.

She and ILI’s other co-founder, Janice Rogers, began the operation in 1984 because they wanted to offer a language program based on student-centered learning. Johnson had taught English in Spain for several years, and both she and Rogers had earned masters at the School for International Training, a Brattleboro, Vermont institute that offers degrees in international education and sustainable development, among other fields.

Those early years “were a real labor of love,” says Johnson, who recalls long work hours for little money, but which were also fueled by “this passion I have for teaching languages.” Yet over time ILI was able to tap a number of funding sources to increase its programming and pay employees better wages: federal and state education monies, grants from different organizations and foundations, tuition, and donations from area businesses and individuals.

“We’ve gotten great support from the community,” says Gear, who points to a new scholarship program funded by Dean Cycon, the president of Dean’s Beans Organic Coffee, the Orange-based company that has built close relationships with small-scale growers across the globe to sell Fair Trade coffee. Cycon, says Gear, is contributing $1,300 a month, over a five-year span, for a scholarship program for selected students in ILI’s accelerated English program, where students spend 21 hours a week over several months studying English.

That program, aimed at foreign students to prepare them for college in the U.S., or for professionals who want to improve their language skills for their jobs, has also been funded through a gift from the United Way, says Gear. “It means a lot to us that people in the community share our vision and goals.”

Over the years, Johnson adds, ILI has sometimes lost money, and the institute has had to scale down some classes, though it’s always bounced back. “The goal was never to make a lot of money,” she adds.

The goal, rather, has been to help a range of people — immigrants, foreign college students, Americans looking to brush up on rusty language skills, businesses trying to serve their employees or customers better — make connections in another language. “It’s about keeping those doors open,” says Johnson.

Steve Pfarrer can be reached at spfarrer@gazettenet.com.

Related Articles

- The Reciprocity of Language Education: Cultivating Tolerance, Compassion, and Humility

- ESL classes: What are the objectives and aims of English language students?

- ILI board president Markus Jones values the power of language

- Brittany opens doors at gender inclusive school

- Driving curriculum and legislative bill aim to expand access to driver’s licenses for immigrants and refugees in Massachusetts!